A Host of Golden Daffodils

The story of a springtime favourite

The daffodil is one of our most iconic flowers. The appearance of its cheerful yellow blooms in our gardens, parks and woodlands announce the arrival of spring and hopefully brighter days to come.

Today, there are almost 27,000 daffodil (Narcissus) cultivars, which come in a dazzling array of shapes and sizes. The UK grows more daffodil crops than any other country – about half of the world’s total.

The most popular garden varieties of daffodil began to emerge in the past 200 years, but their story goes back much further. Read on to discover the fascinating history of one of our favourite springtime flowers told through daffodil art from the RHS Lindley Library Collections.

Defining daffodils

The 'daffodowndilly', the ‘Flower of March’, the ‘trumpet flower’… the daffodil has gone by many names.

However, a frequent misconception is that there is a difference between daffodils and narcissi. Narcissus is simply its Latin or botanical name and daffodil is its common name.

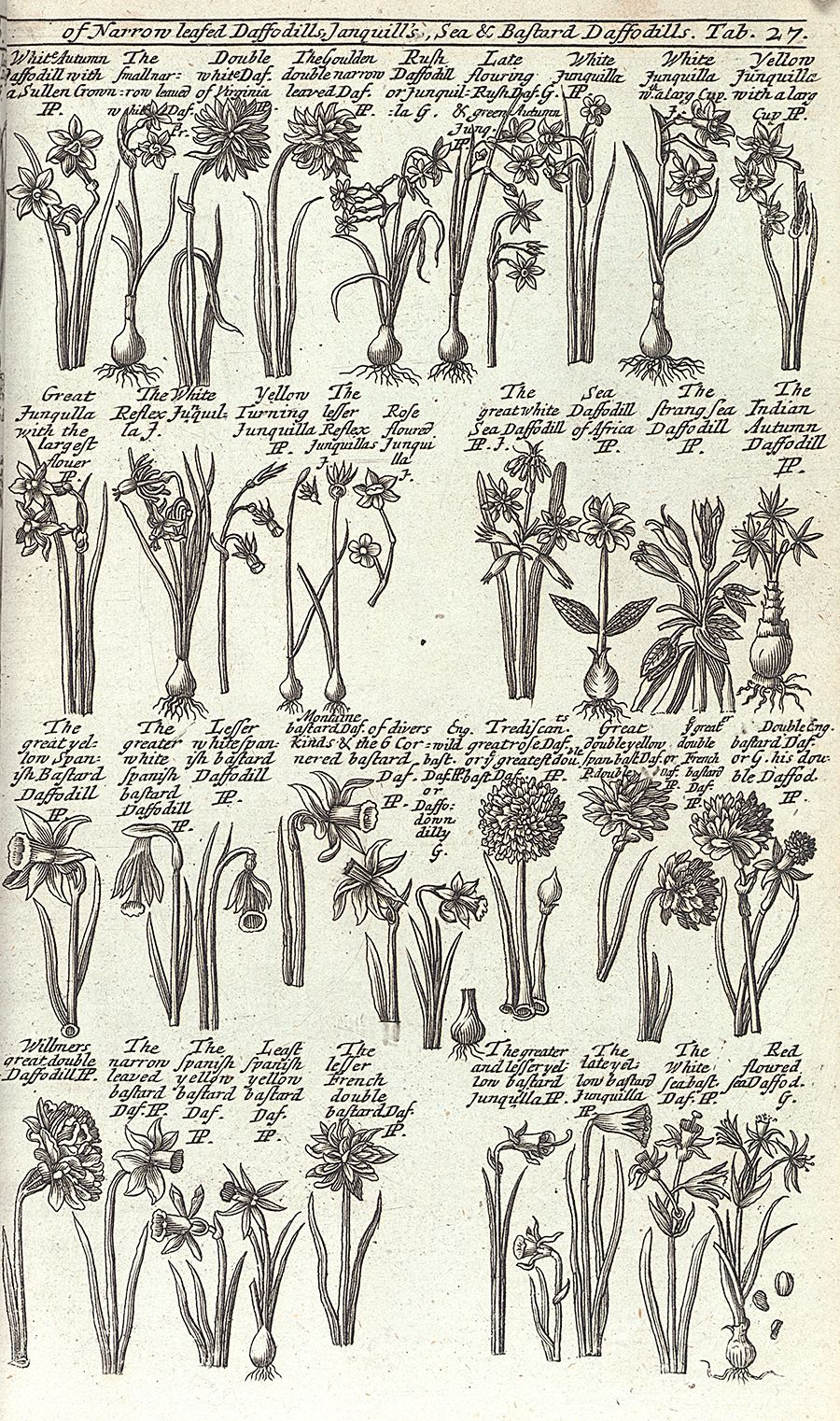

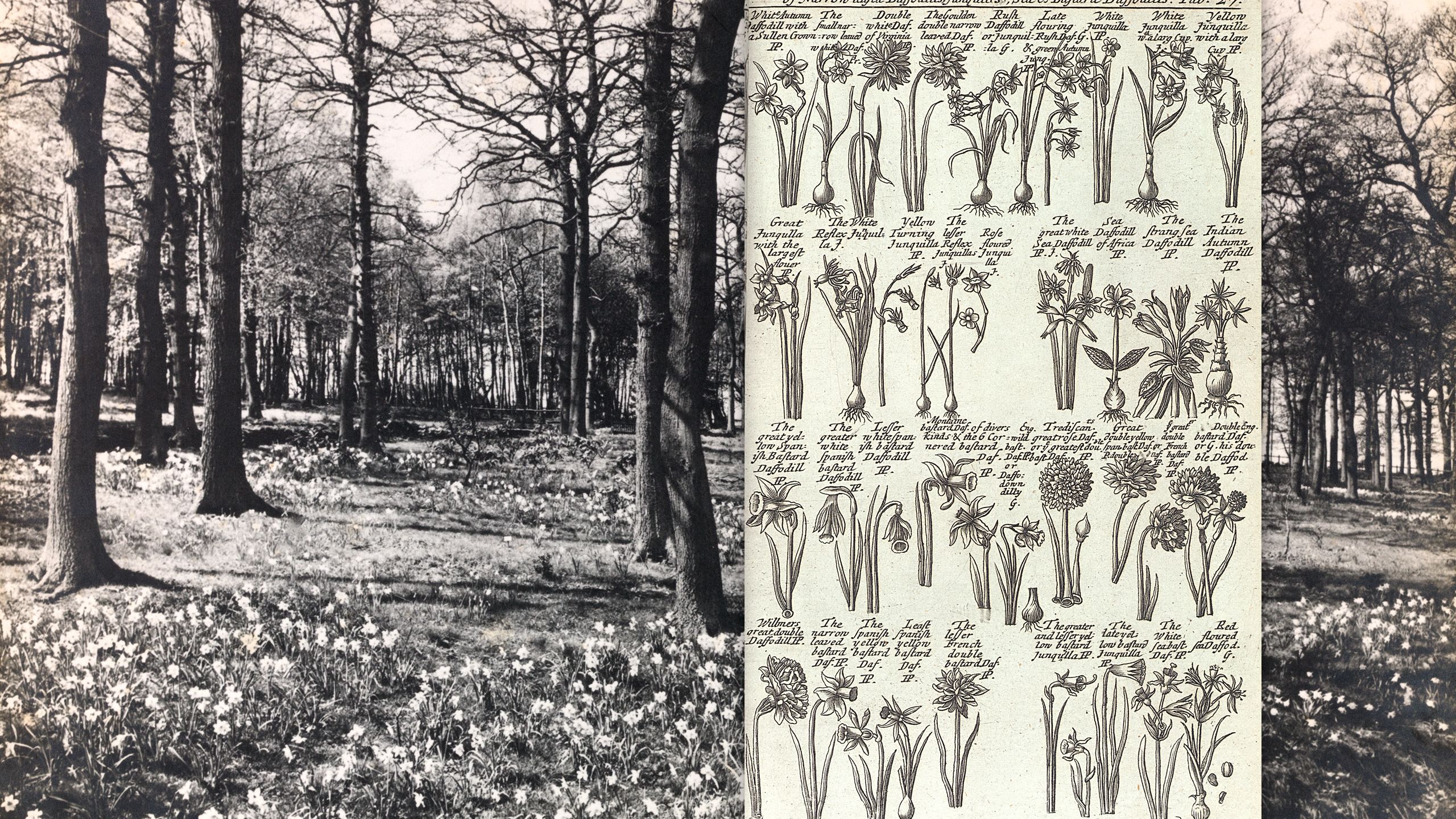

- Image: Printed engraving of different Narcissus types, from A Compleat Herbal by James Newton, 1752. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections

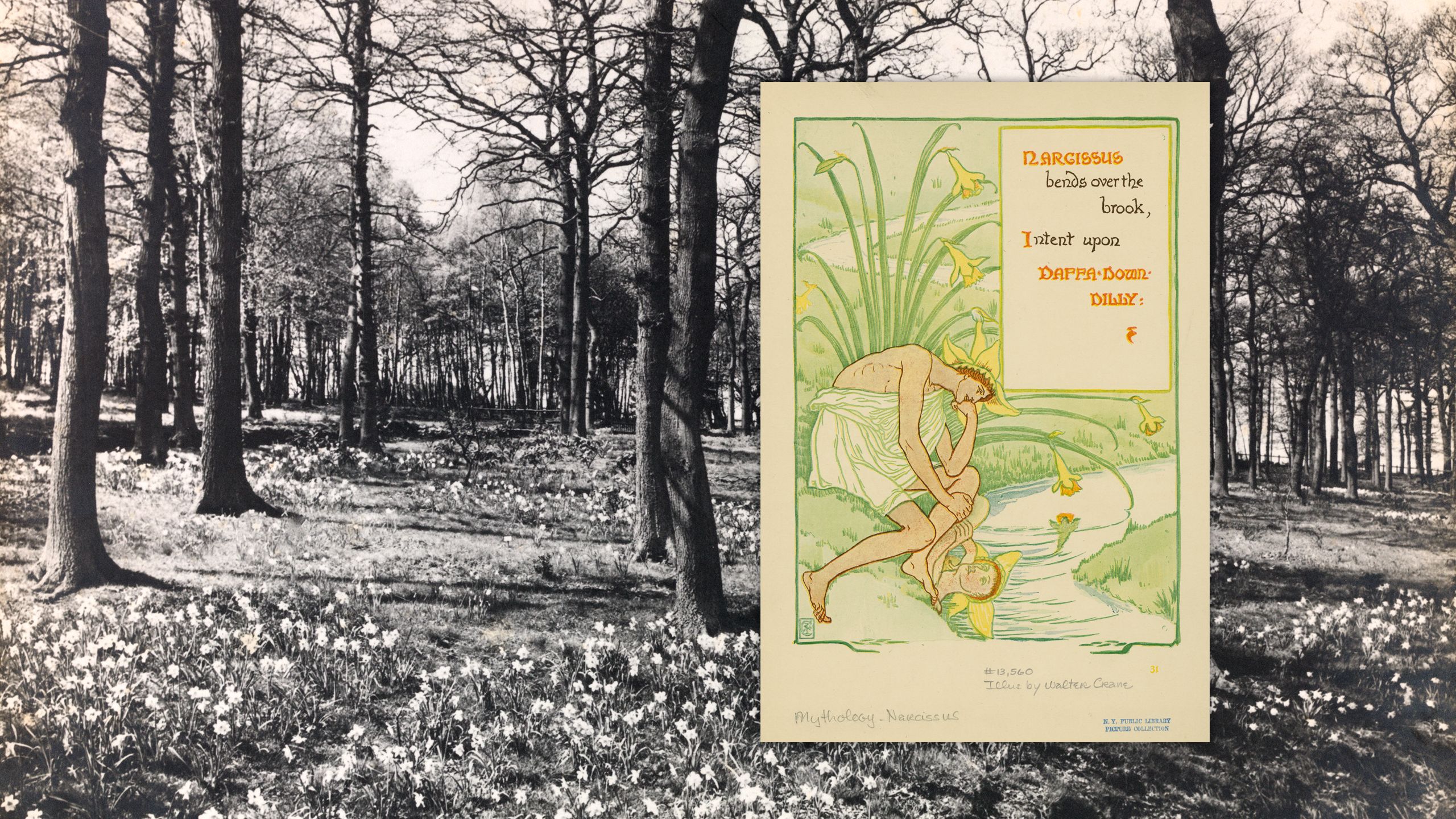

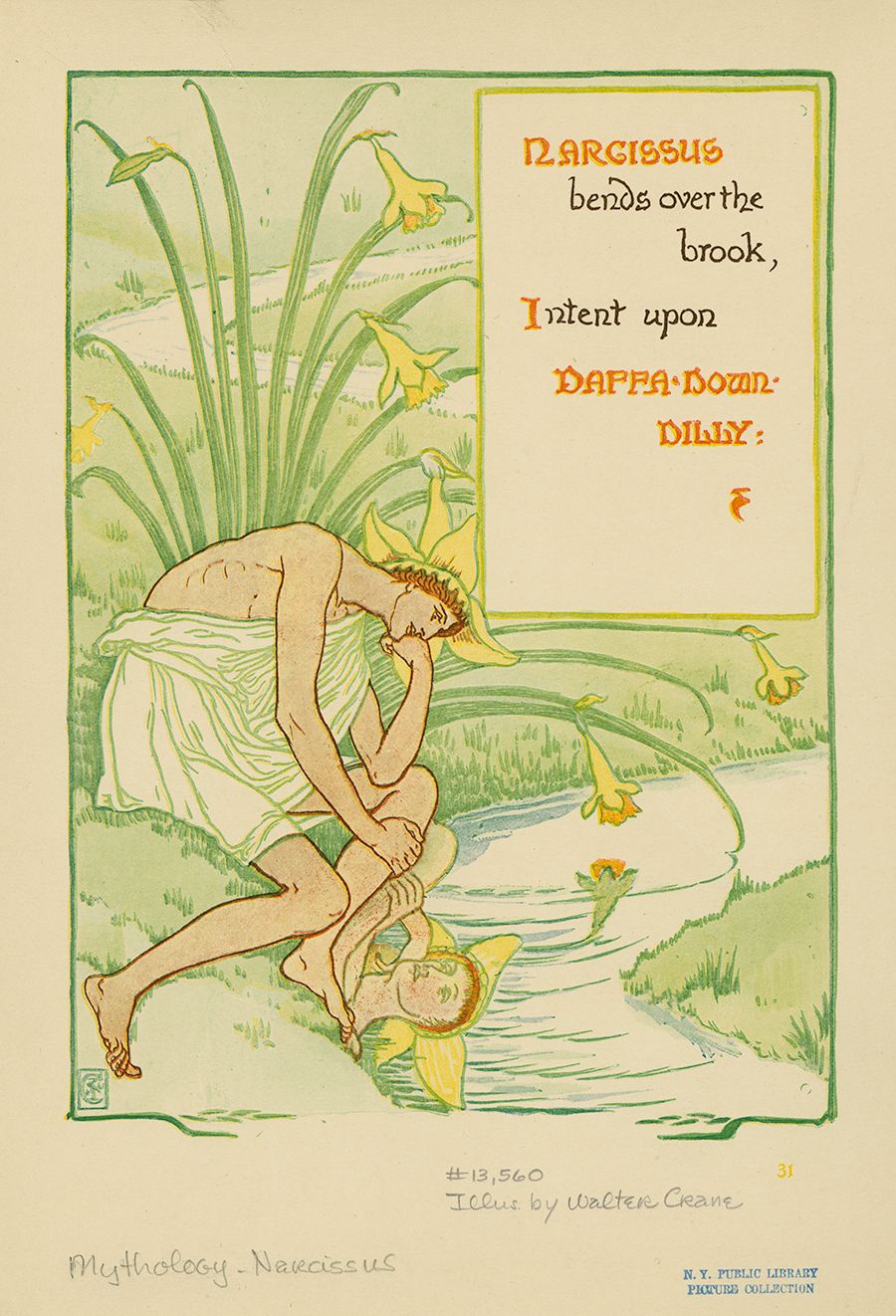

Its Latin name has long associated the daffodil with the Greek myth of the youth Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection and languished away by a pool of water. A Narcissus flower is said to have sprung from where he died.

However, unlike the classic yellow daffodils in this illustration, the flower in the legend was probably the white and orange Narcissus tazetta, which is known to have grown in ancient Greece.

- Image: Colour illustration from A Floral Fantasy from an Old English Garden, by Walter Crane, 1899. Credit: The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Another explanation behind the daffodil's Latin name is its link with the Greek word narco, which is the root of the word ‘narcotic’ or ‘becoming numb’. The daffodil is poisonous and this is one of a number of symptoms if eaten.

Nonetheless, the daffodil has been cultivated for thousands of years by some of the earliest civilizations, usually for medicinal and religious rather than ornamental purposes.

- Image: Colour engraving of Narcissus tazetta: ‘Chinese daffodil/Chinese lilly’, from Collection precieuse et enluminée des fleurs… by Pierre Joseph Buchoz, 1776. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Wild Daffodils

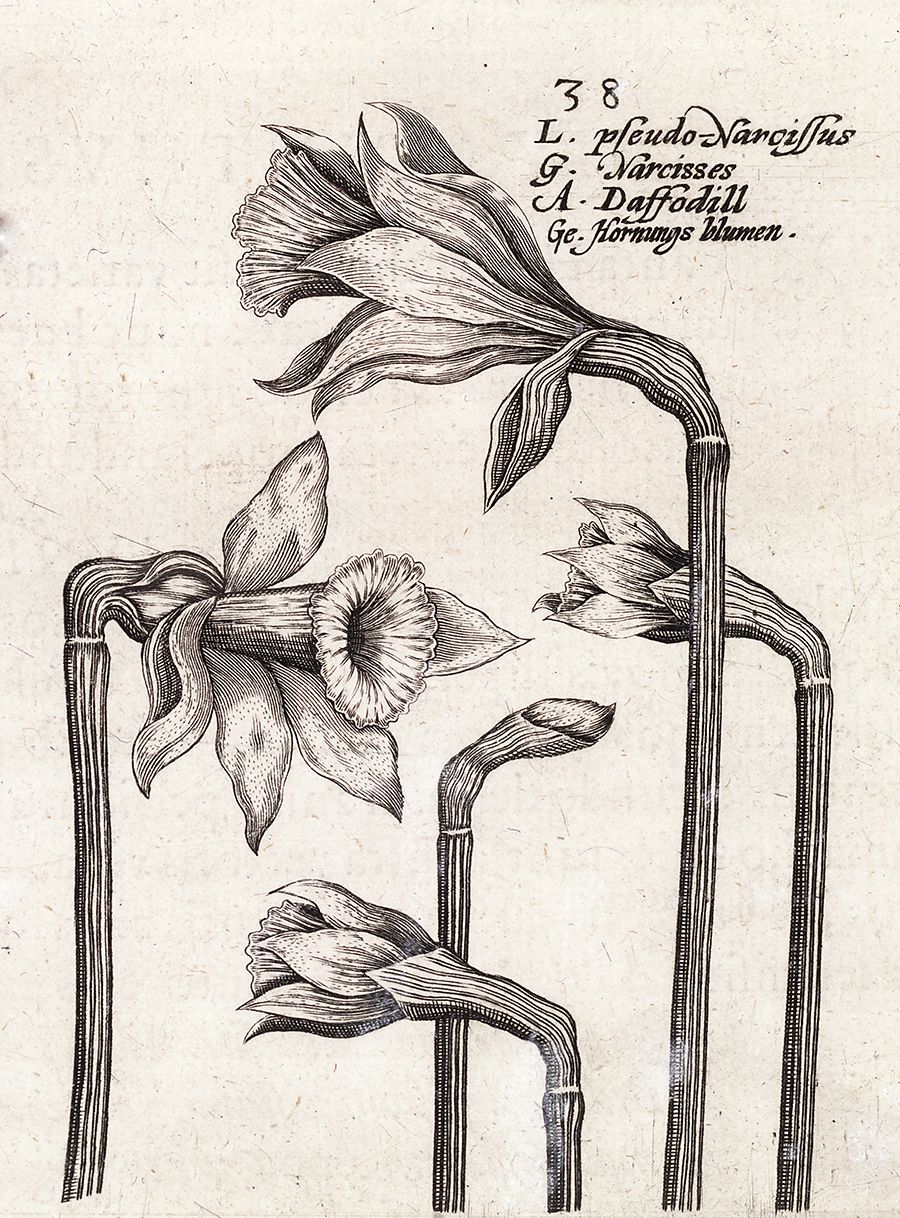

Wild daffodils first grew in Spain and Portugal before spreading across Europe. Wordsworth’s host of golden daffodils, were almost certainly one of the most pervasive of these wild species, the Narcissus pseudonarcissus.

- Image: Engraved illustration of Narcissus sorts, described as pseudonarcissus. Drawn and engraved by Crispijn de Passe the Younger. From Hortus Floridus (Arnheim, 1614). Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Sometimes called ‘Lent Lilies’, these familiar flowers grew all over Britain until the 19th century. Since then wild populations have declined sharply due to agriculture, woodland clearances and the uprooting of bulbs for gardens.

- Image: Watercolour of Narcissus pseudonarcissus (the common daffodil, lent lily or averill) painted in Sussex by Lilian Snelling, probably in the early 1900s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Daffodils enter the garden

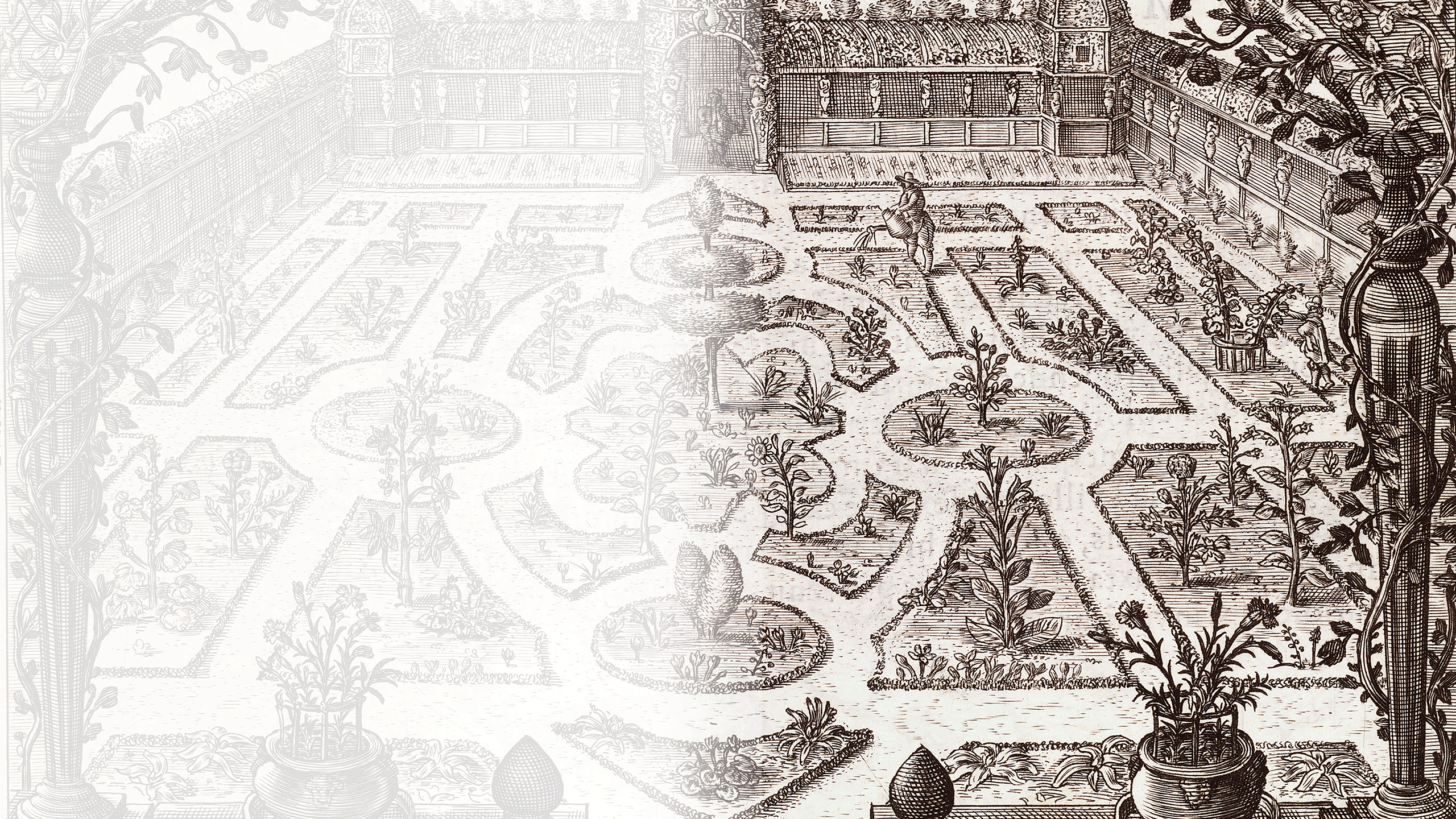

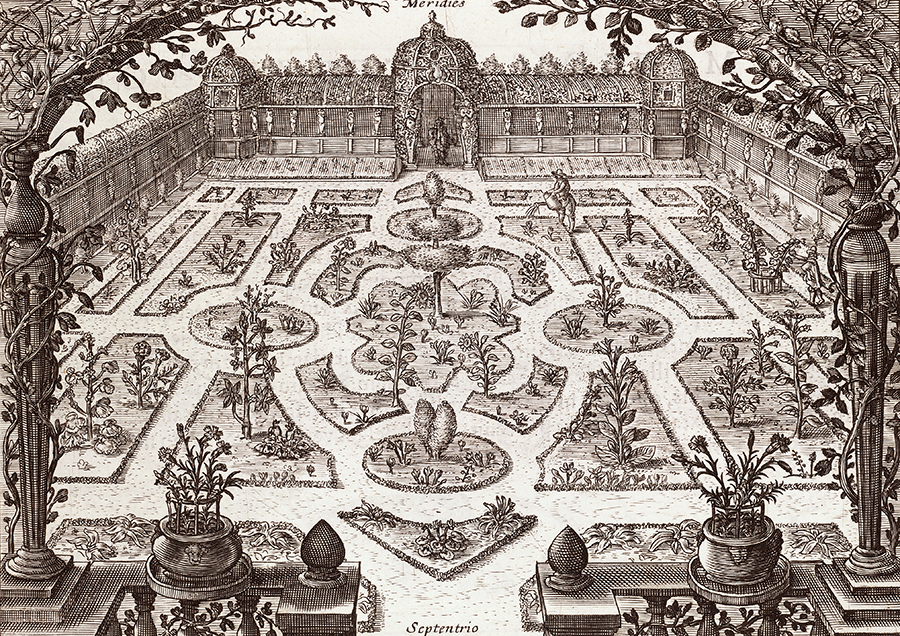

It is quite a surprise that the daffodil first became a popular garden plant in the Tudor and Elizabethan eras. Its natural appearance was far less suited to the geometrical patterns and symmetry of the formal garden styles of the time than other bulb plants like the tulip.

- Image: Engraving of a 17th-century garden scene from Hortus Floridus by Crispijn de Passe the Younger, 1614. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

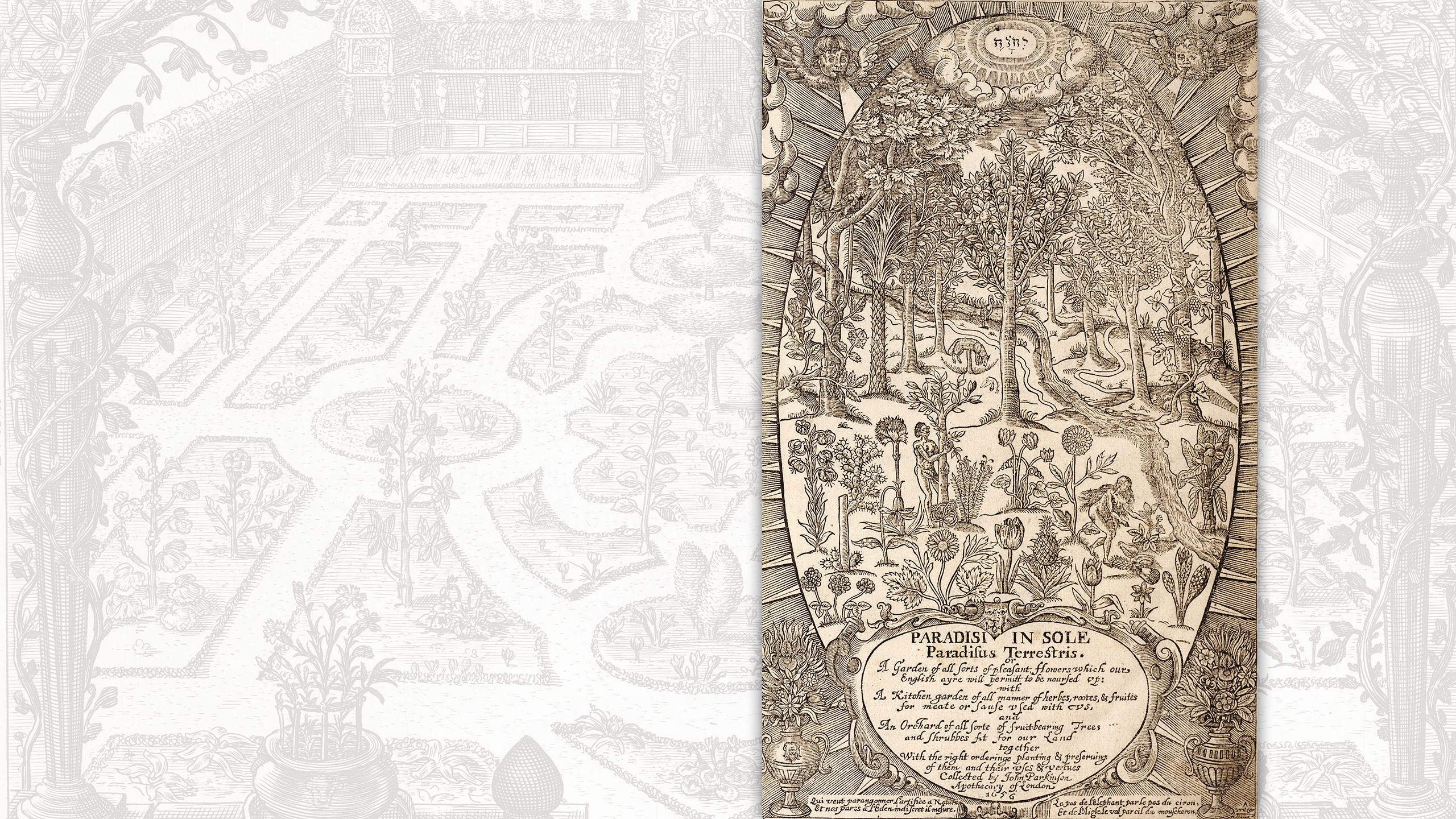

However, the daffodil found an important champion in the figure of John Parkinson – who became Apothecary to King James I. His Paradisus Terrestris was the first book in English concerned with the ornamental rather than medicinal uses of plants.

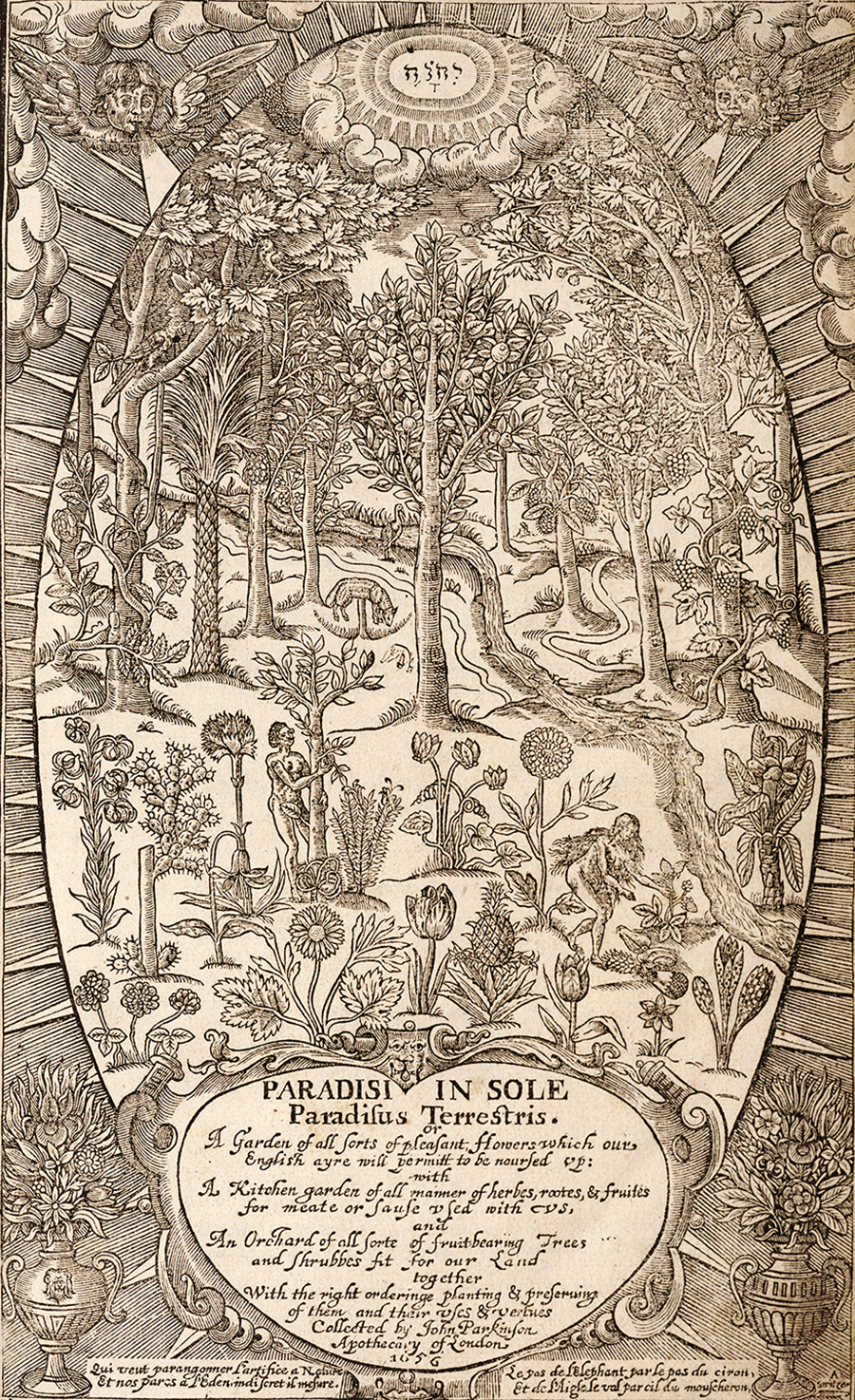

- Image: Title page from John Parkinson’s Paradisi in Sole: Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 editon. The title is a pun on Parkinson’s name and translates as ‘Park-in-Sun’s Earthly Paradise.’ Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

“There hath beene great confusion among many of our modern Writers of Plants in not distinguishing the manifold varieties of Daffodils.”

In his own book, Parkinson identified almost one hundred different varieties of daffodil then growing in England.

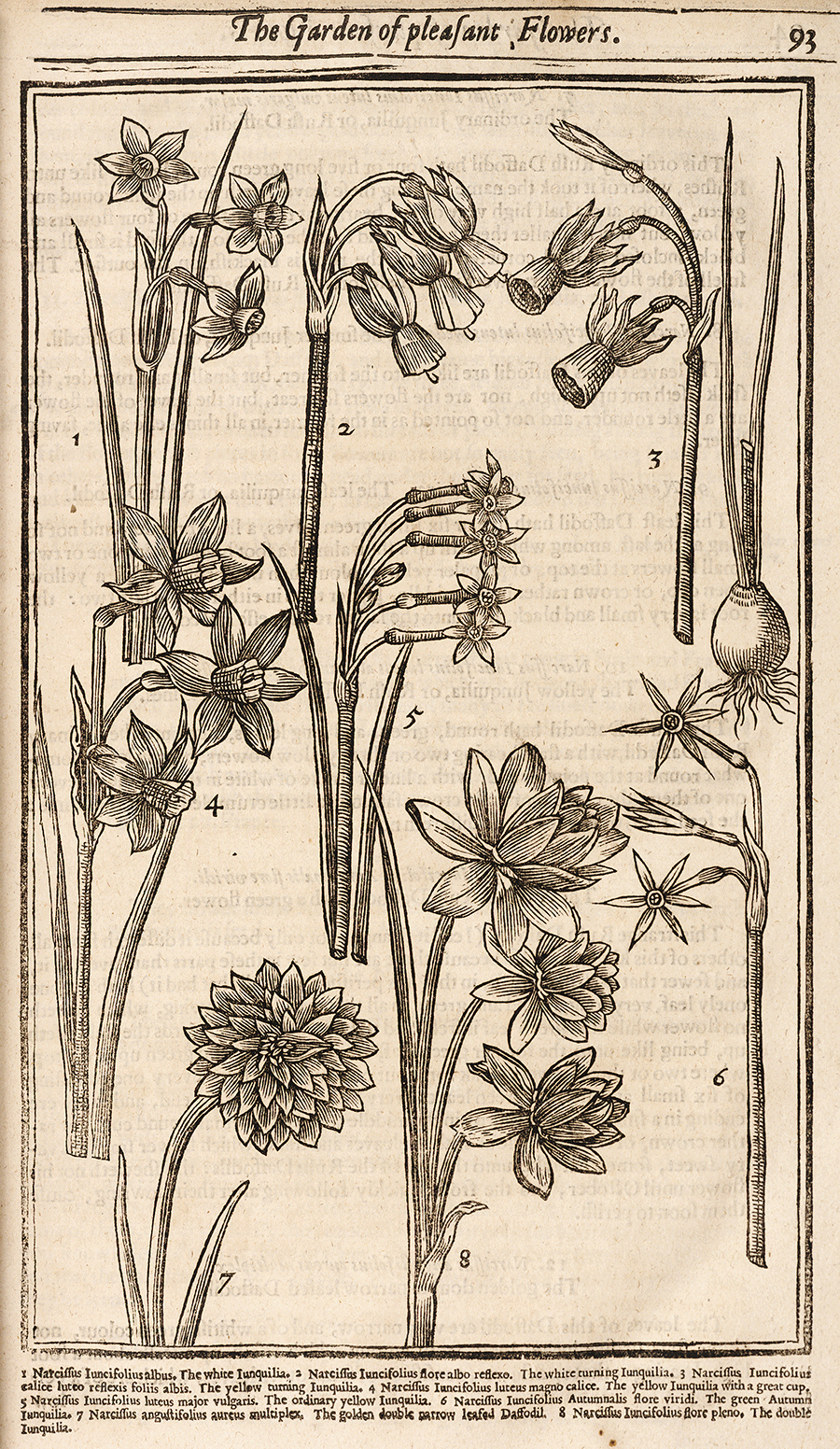

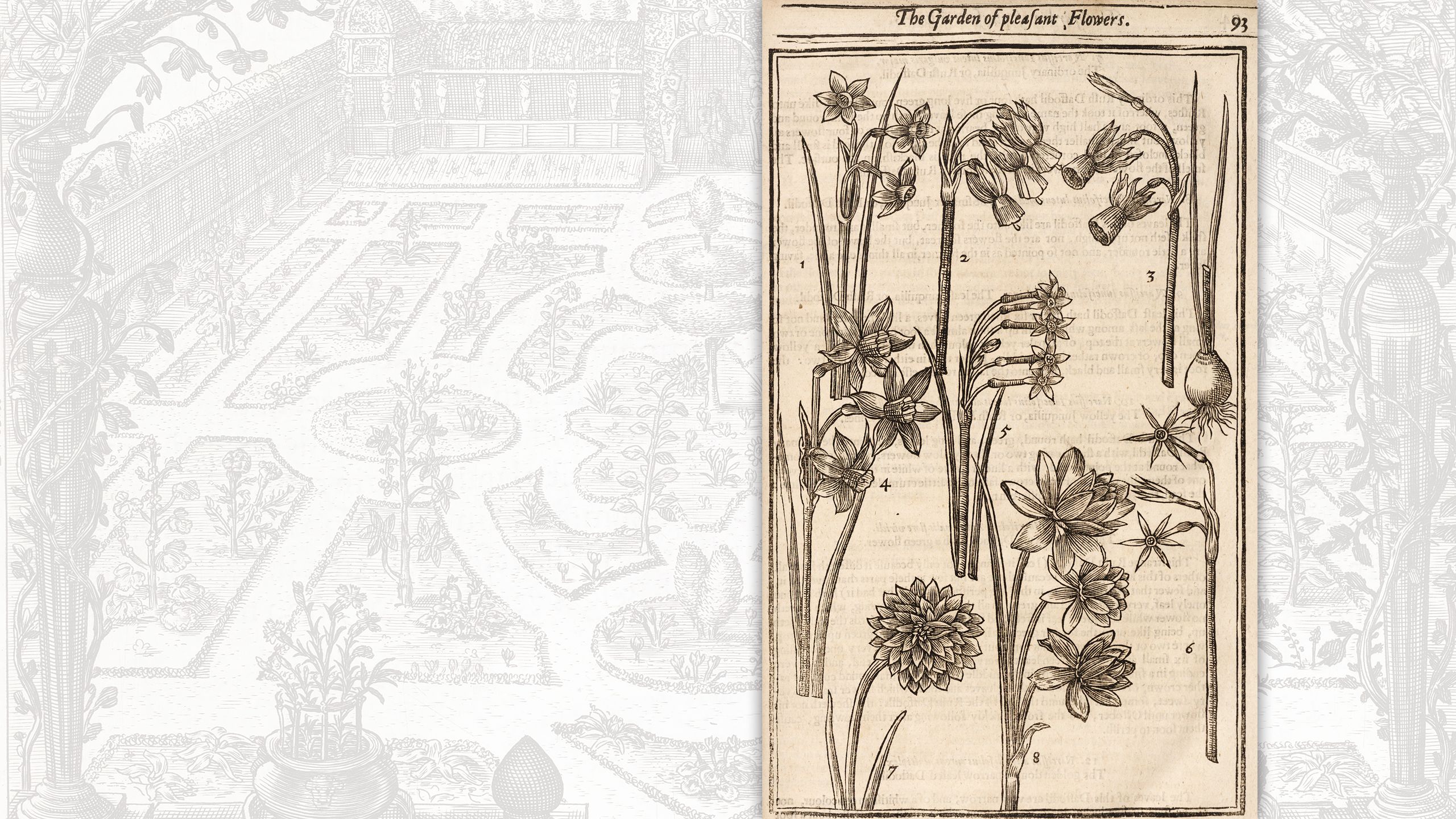

- Image: Wood engraving of eight Narcissus sorts from John Parkinson’s Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 edition. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Between the late 1600s and early 1800s, many of these old varieties fell out of fashion and were lost forever.

However, Parkinson’s work would later inspire some of the most important daffodil breeders of modern times.

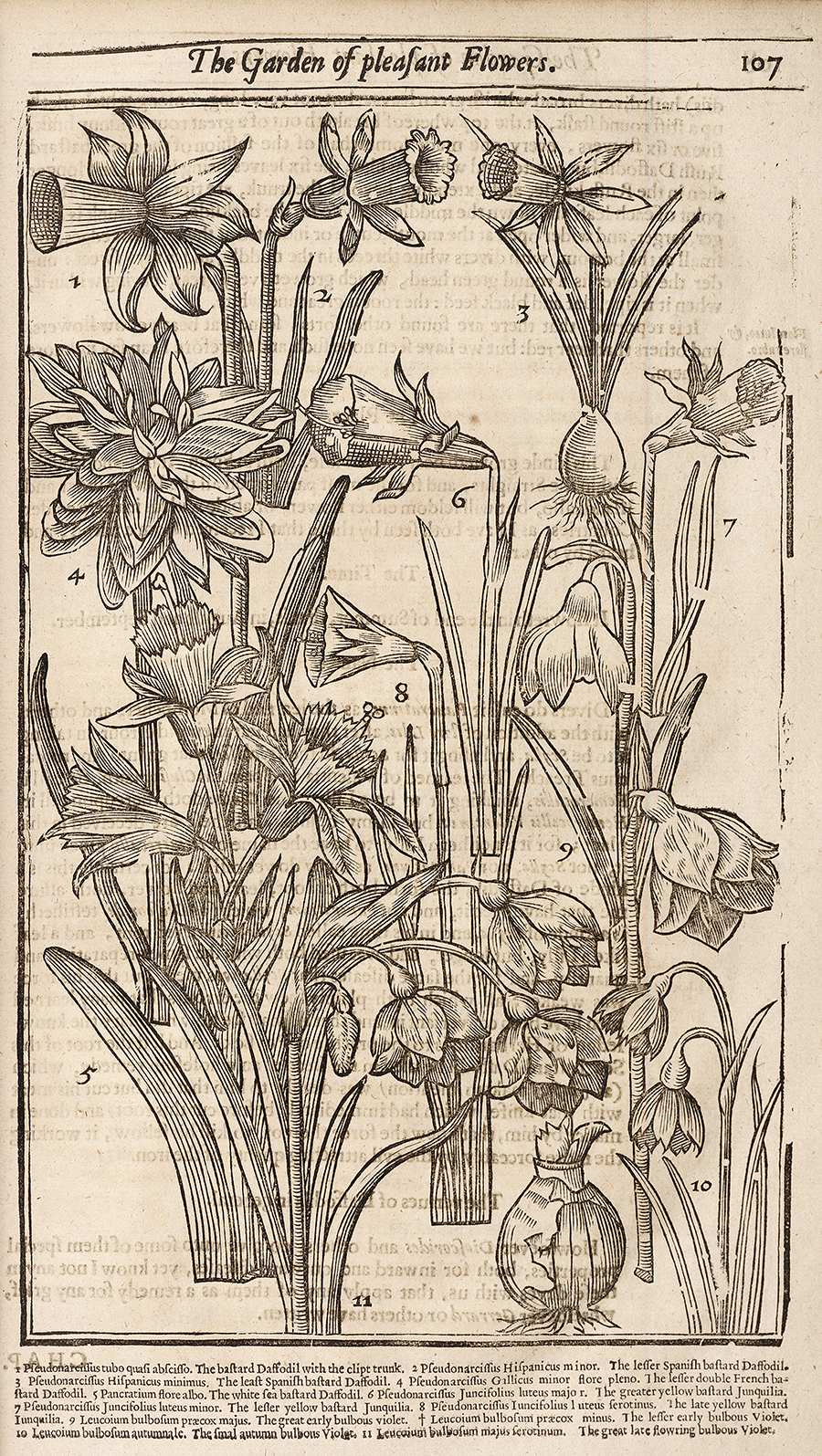

- Image: Wood engraving of eight Narcissus sorts from John Parkinson’s Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 edition. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

The first daffodil hybrids

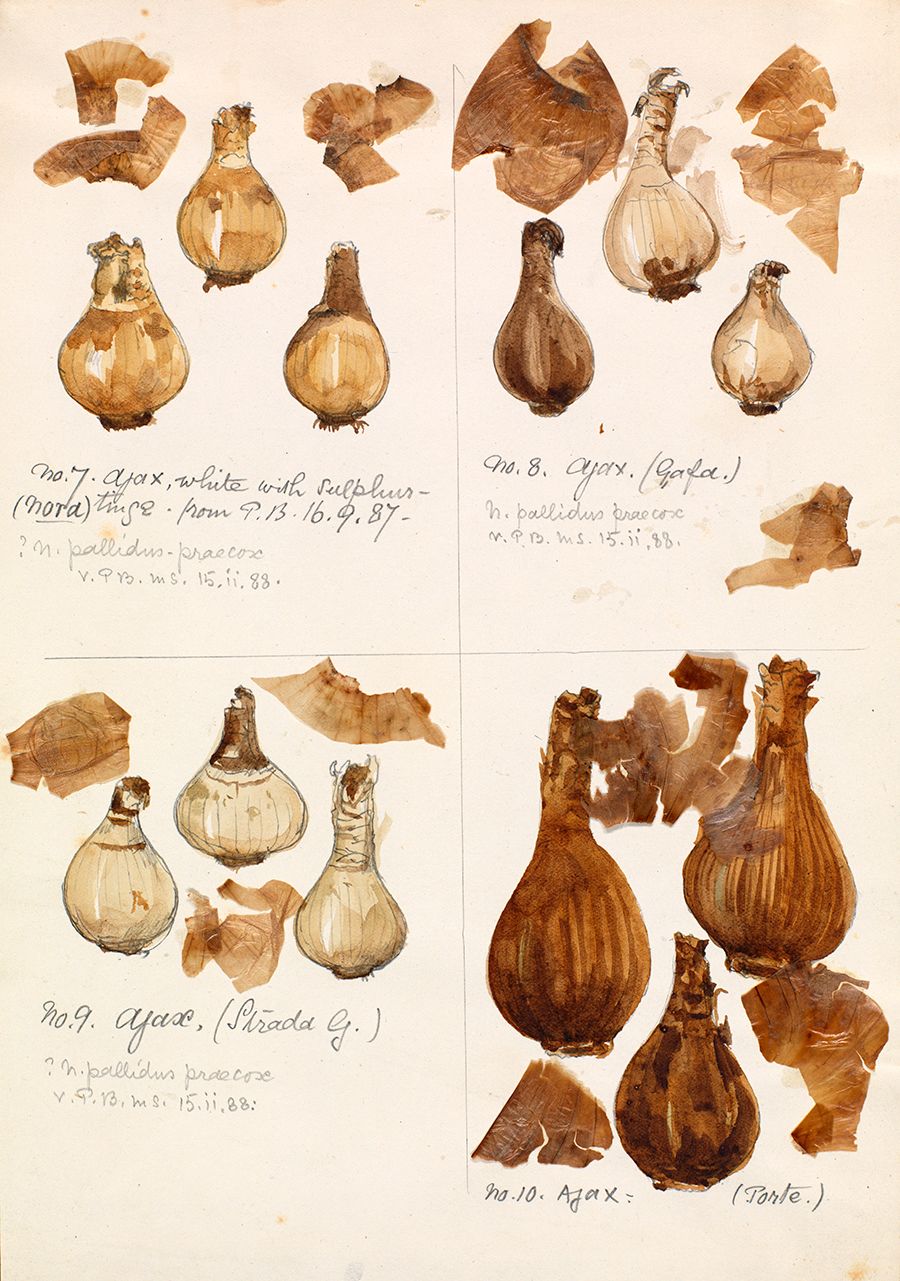

Daffodils are not a quick plant to hybridise as it can take several years to flower them from seed.

The new rage for plant breeding in the early 1800s initially had little room for the daffodil – the focus was on exotic (and expensive) plants like orchids from far-flung parts of the globe.

- Image: Watercolour sketch of Narcissus bulbs by Frederick William Burbidge, late 1800s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Daffodil breeding was a quieter revolution. It started in the 1830s, with a Church of England clergyman.

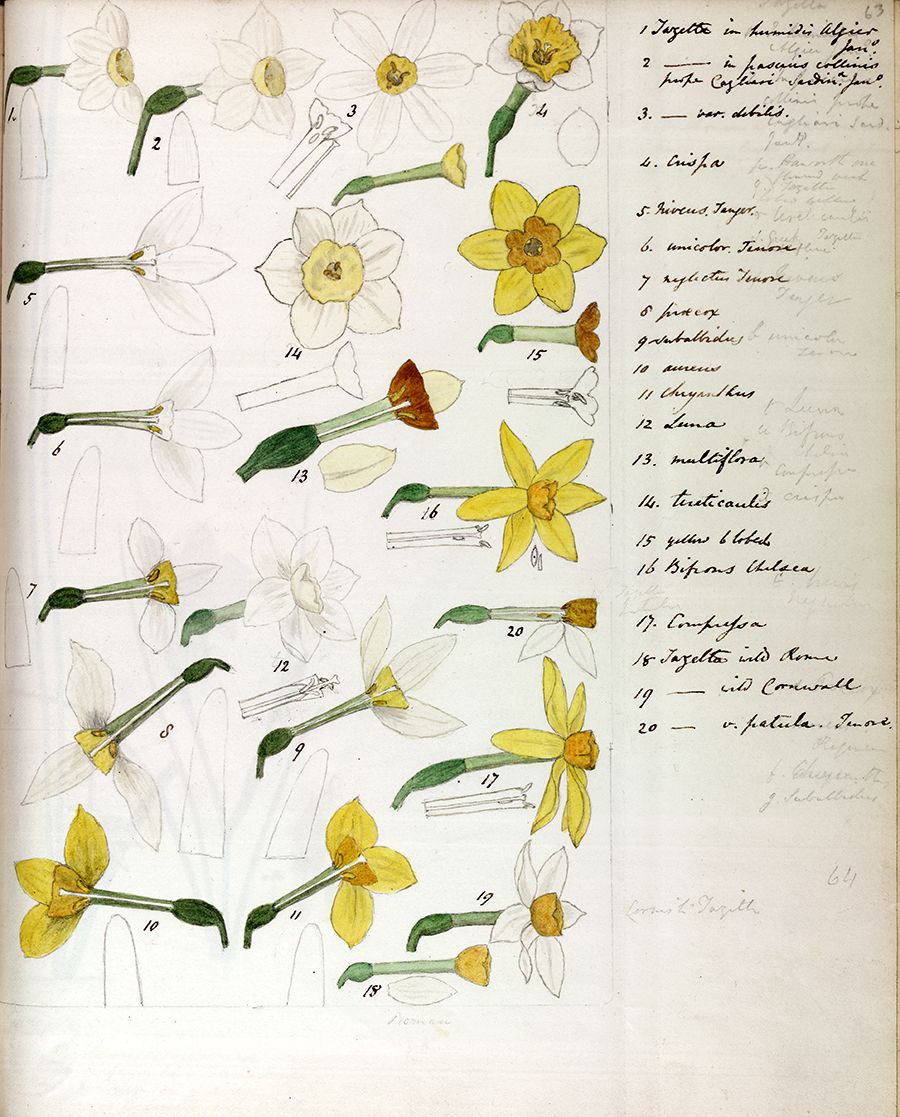

- Image: Pencil and watercolour sketches of Narcissus varieties by Dean William Herbert, 1847. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

While Dean of Manchester, William Herbert (1778–1847) successfully cultivated several new daffodil hybrids and pioneered new ways of classifying them.

The Dean’s botanical breakthroughs were admired by Darwin and paved the way for the explosion of daffodil breeding later in the 19th century.

- Image: Pencil and watercolour sketches of Narcissus varieties by William Herbert, 1847. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

The Daffodil King

Even after William Herbert, the daffodil continued to be seen as a wild flower that was out of place in the formal gardens that were fashionable in the Victorian era.

There were few British suppliers of daffodil bulbs and few gardeners wanting to buy them.

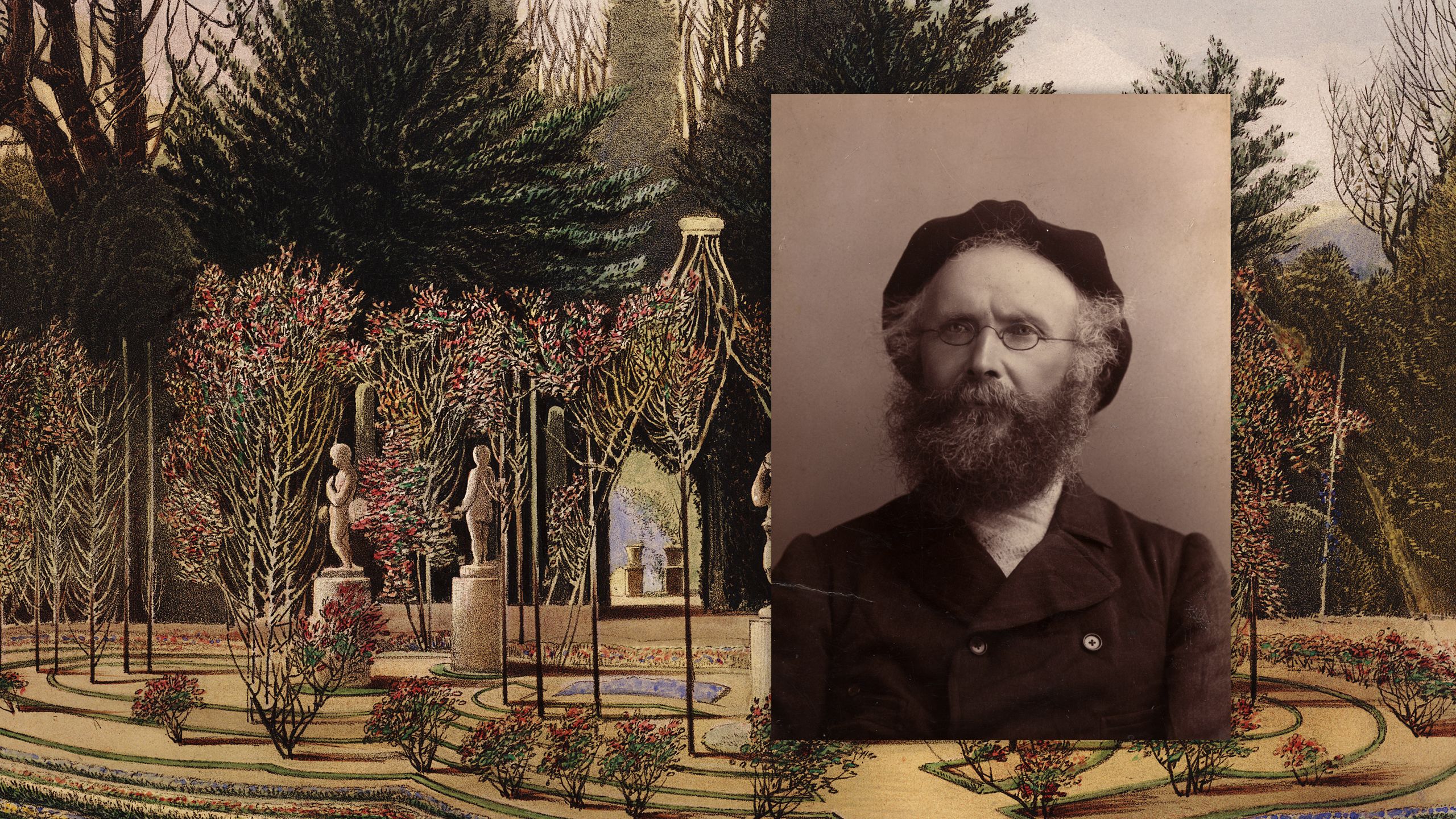

- Image: Chromolithograph of ‘The Rose Garden, Nuneham’, in The Gardens of England (London, 1856-57) by Edward Aveno Brooke. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

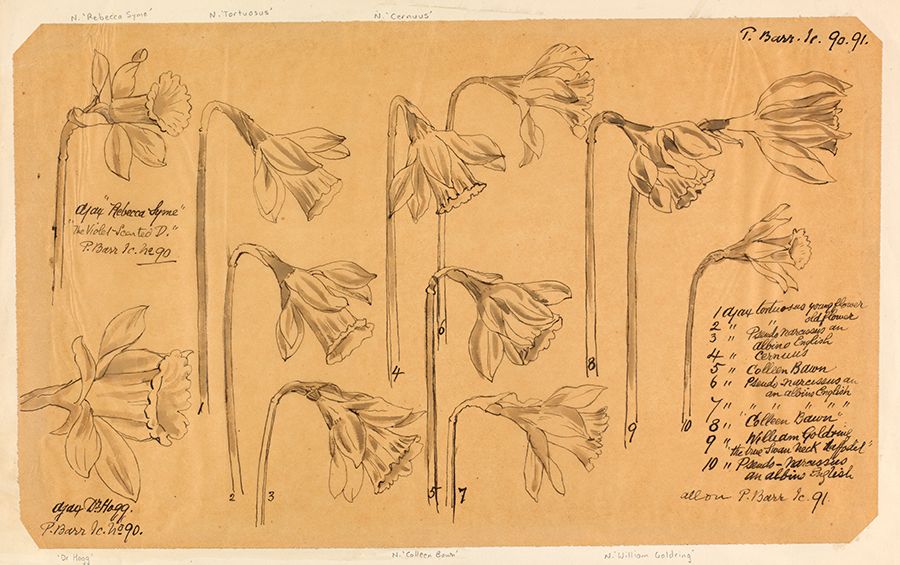

One of the first to change the tide of popular opinion against the daffodil, was the Scottish nurseryman, Peter Barr (1826 – 1909).

- Image: Photograph of Peter Barr, about 1900. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Inspired by the long-lost daffodil varieties that John Parkinson had identified 200 years earlier, Peter Barr built up his own daffodil collection.

He purchased new daffodil hybrids raised by British growers, saving many of them from destruction.

- Image: Watercolour of Narcissus Leedsii ‘Superbus’ by William Caparne, about 1884-85. One of a number of paintings that Peter Barr commissioned of the rare collection of daffodils that he had purchased from the prolific English daffodil breeder, Edward Leeds (1802 – 1877). Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Barr's successful nursery business and slickly produced bulb catalogues did much to increase the public appetite for daffodils. They also vastly improved the system by which new daffodil hybrids were classified.

- Image: A watercolour of a daffodil hybrid named after Peter Barr from his own album of daffodil paintings, early 1900s (artist unknown). The Narcissus ‘Peter Barr’ is described as ‘a grand variety, raised at our nurseries, flower large, bold and handsome’. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

The first Daffodil Conference

“The Narcissus… is now reasserting its position, and claiming its proper place in the general economy of border decoration, and as a cut flower for furnishing vases”

In 1884, Peter Barr persuaded the RHS to hold its first Daffodil Conference – a visually spectacular event held in a large conservatory at the Society’s South Kensington Gardens. It included breathtaking displays from the likes of Gertrude Jekyll who filled the space with a sea of daffodils in waves of yellow, orange, white and gold.

Perhaps most importantly, the Conference led to the establishment of the first RHS Daffodil Committee who would oversee a new official classification framework for daffodils.

From this point on, the RHS would name and register all new Narcissus hybrids.

- Image: Daffodils on display at the RHS London Spring Plant and Orchid Show, 2017. Credit: RHS / Luke MacGregor.

The RHS Daffodil Committee included trailblazing daffodil breeders like Sarah Elizabeth Backhouse (1857–1921).

Already an established daffodil breeder herself, Sarah Elizabeth Dodgson had married into the prolific daffodil growing family, the Backhouses, who bred over 470 new Narcissi hybrids between them.

- Image: Photograph of Sarah Elizabeth Backhouse, late 1800s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Sarah Backhouse pioneered the breeding of red-cupped daffodils and 2 years after her death, her husband named the first ever pink-cupped daffodil in her memory.

- Image: Plant portrait of Narcissus ‘Mrs R.O. Backhouse’. Credit: RHS / Philippa Gibson.

Daffodil artists

From early on, artists played an important role in the identification and classification of new daffodil hybrids.

Some of the beautifully accurate daffodil paintings in the RHS Lindley Collections have been used by the current RHS Bulb Committee (the successor to the RHS Daffodil and Tulip Committee) to identify the characteristics of lost daffodil varieties and to add them to the RHS Daffodil Register.

- Image: Official RHS portrait of Narcissus ‘Diolite’, which received an award of merit on 6 April 1932, by Elsie Katherine Kohnlein. Credit: RHS / Elsie Katherine Kohnlein.

This graceful daffodil portrait is by an unnamed chinaware painter who worked in the factories of the pottery manufacturer, William Copeland (1872–1953).

Copeland was a renowned daffodil breeder who commissioned a large collection of these portraits to capture the daffodil varieties grown by himself and others at the turn of the 20th century.

The artist is now lost to history but,in precisely capturing its characteristics, their work has allowed a daffodil that is now out of cultivation to be added to the RHS Daffodil Register.

- Image: Watercolour of Narcissus ‘Linnaeus’ and a Pyrenean Narcissus poeticus by an unnamed artist, about 1895–1907. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

This late 19th-century daffodil portrait by the talented botanical artist, Margaret Dickinson, is also a type specimen, capturing the qualities of the now lost Narcissus ‘Carnbie’.

However, this delicate painting is also a reminder of the environmental impact of the daffodil craze at the end of the 19th century.

Dickinson records that the daffodil was grown from a ‘root gathered in Spain by Mr Peter Barr in 1888.’ Later in his career, Barr collected and imported many wild daffodils from Spain and Portugal, which may have enriched daffodil cultivation but had a far less positive impact on native wild populations of daffodils.

- Image: Watercolour and pencil portrait of Narcissus 'Carnbie’ by Margaret Rebecca Dickinson, 1889. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Registering Daffodils today

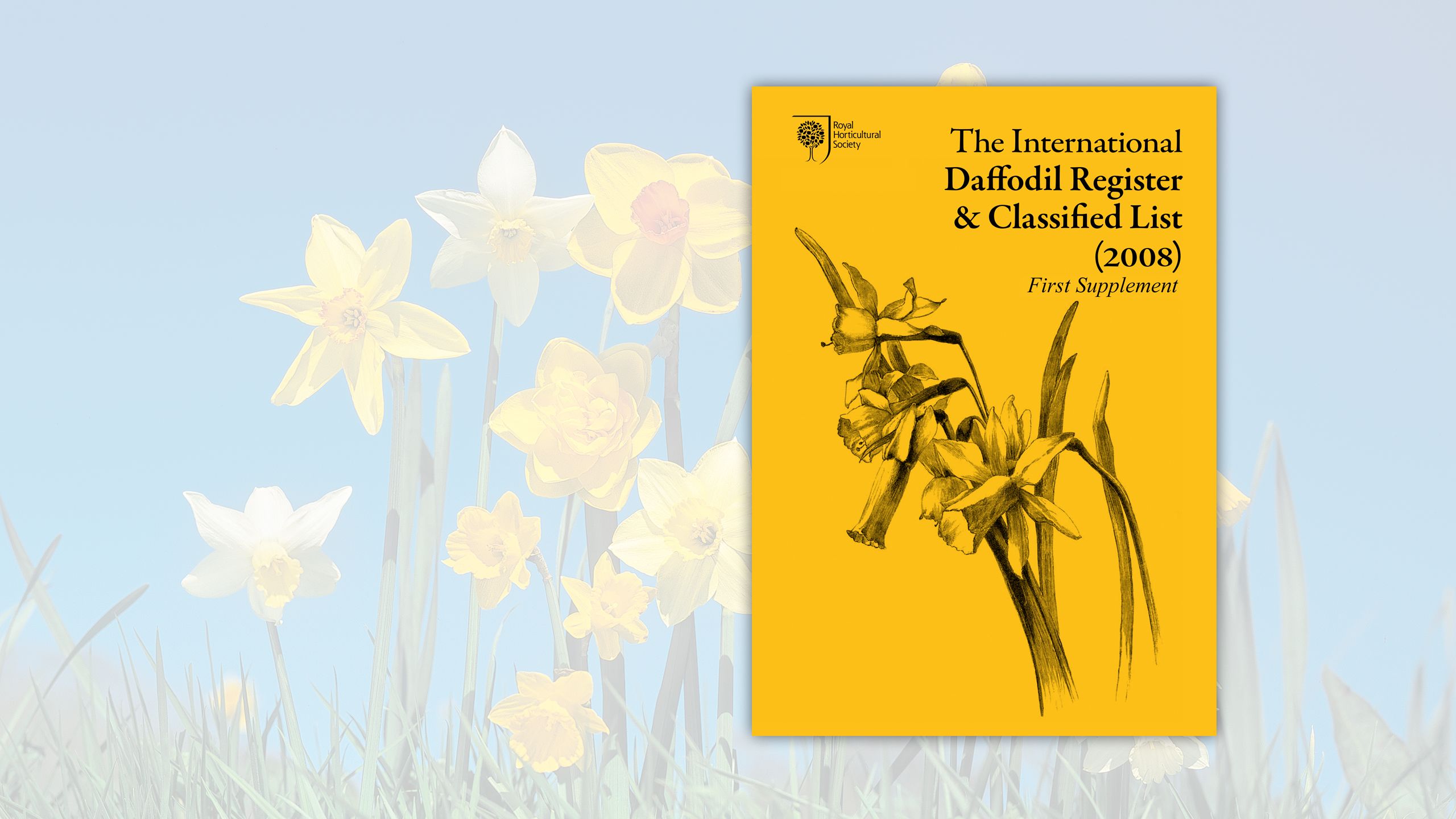

The RHS has been the International Cultivar Registration Authority for Daffodils since 1955.

The Society maintains the International Daffodil Register listing 27,000 named cultivars. The register is searchable online.

- Background image credit: RHS / Tim Sandall.

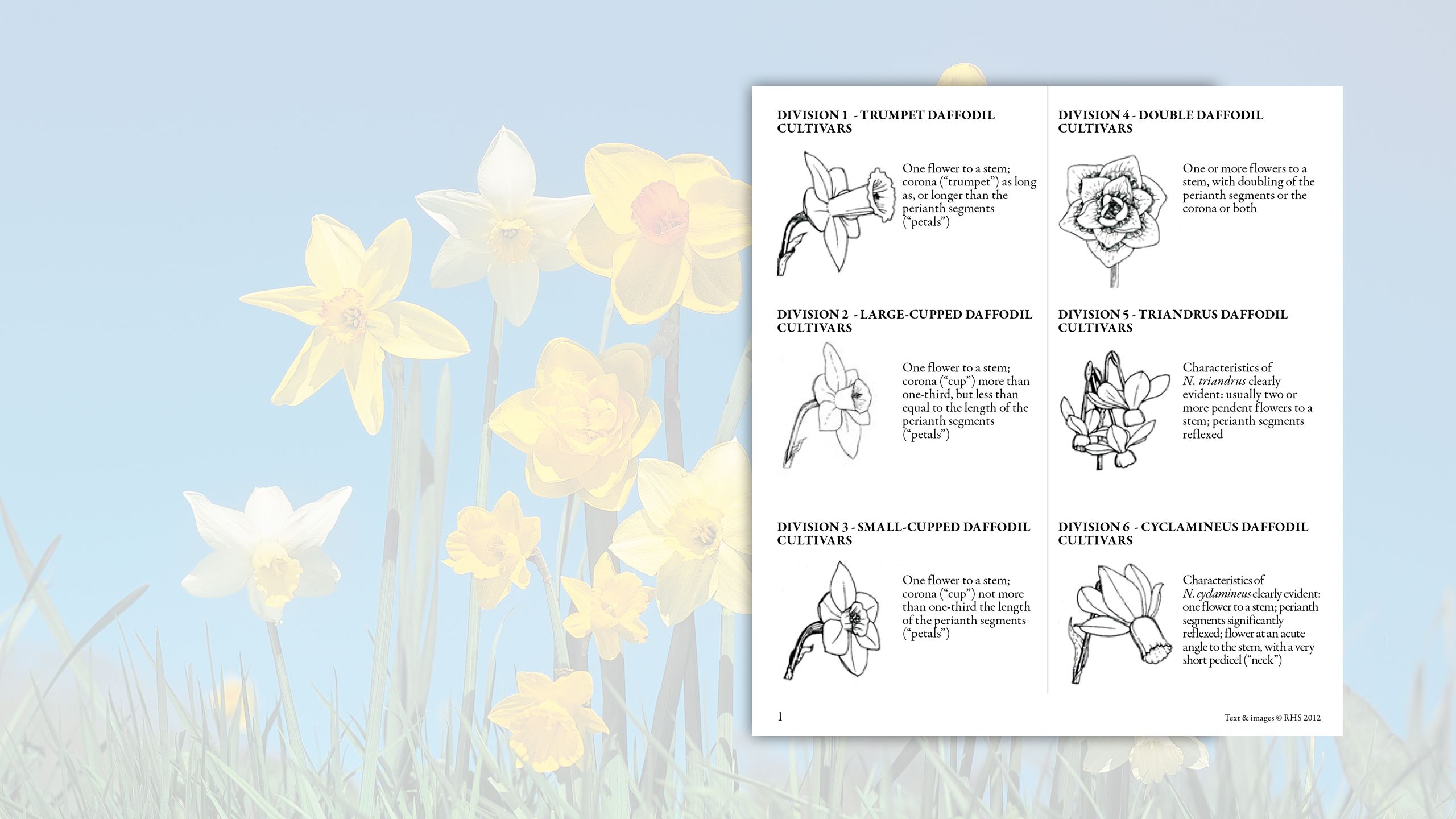

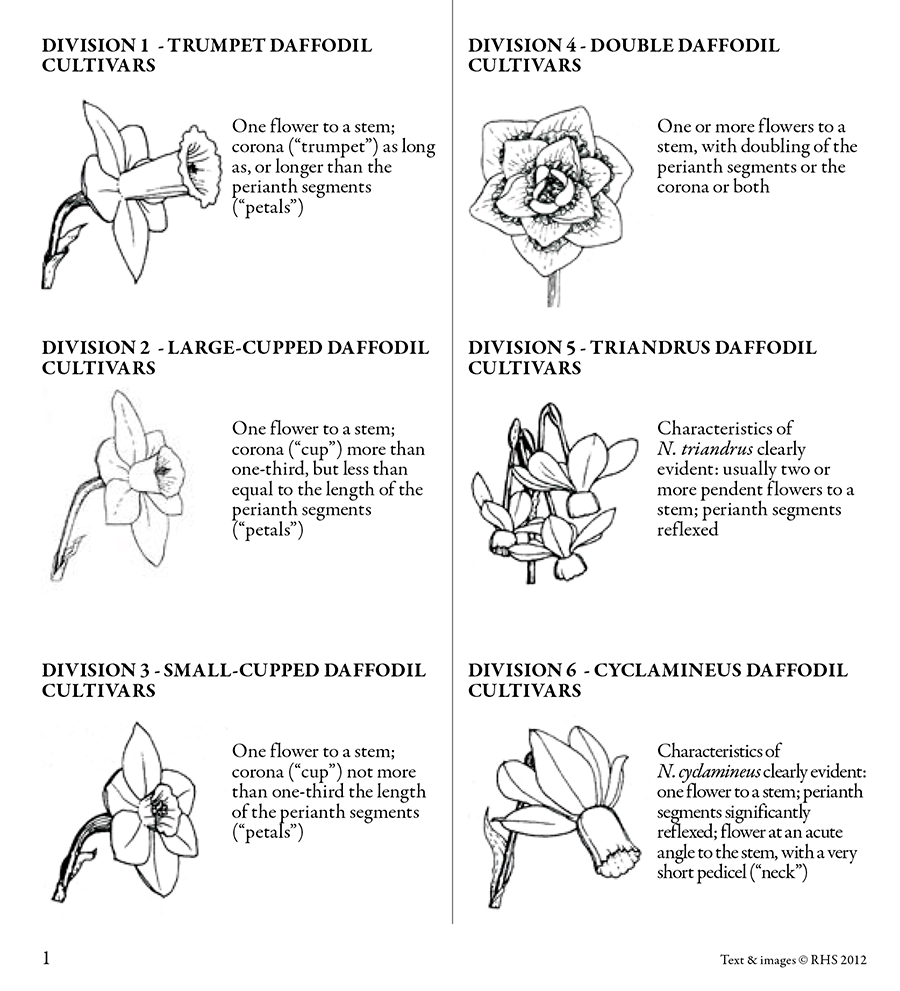

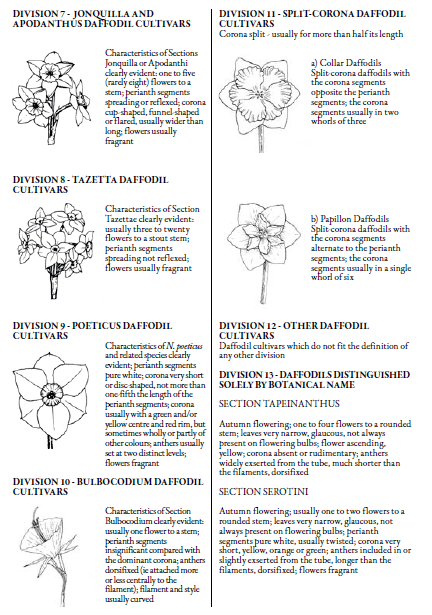

New daffodil cultivars are registered by shape and colour. They are divided into 13 divisions according to characteristics such as corona (or 'trumpet') size and the length of the petals.

Beyond the world of the Narcissus specialist, the daffodil has never been more popular. It remains one of our favourite garden plants, appearing in over 80% of British gardens.

Defining Daffodils

The 'daffodowndilly', the ‘Flower of March’, the ‘trumpet flower’… the daffodil has gone by many names.

However, a frequent misconception is that there is a difference between daffodils and narcissi. Narcissus is simply its Latin or botanical name and daffodil is its common name.

Printed engraving of different Narcissus types, from A Compleat Herbal by James Newton, 1752 Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Printed engraving of different Narcissus types, from A Compleat Herbal by James Newton, 1752 Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Its Latin name has long linked the daffodil with the Greek myth of the youth Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection and languished away by a pool of water. A Narcissus flower is said to have sprung from where he died.

However, unlike the classic yellow daffodils in this illustration, the flower in the legend was probably the white and orange Narcissus tazetta, which is known to have grown in ancient Greece.

Colour illustration from A Floral Fantasy from an Old English Garden, by Walter Crane, 1899. Credit: The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Colour illustration from A Floral Fantasy from an Old English Garden, by Walter Crane, 1899. Credit: The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Another explanation behind the daffodil's Latin name is its association with the Greek word narco, which is the root of the word ‘narcotic’ or ‘becoming numb’. The daffodil is poisonous and this is one of a number of symptoms if it is eaten.

Nonetheless, the daffodil has been cultivated for thousands of years by some of the earliest civilizations, usually for medicinal and religious rather than ornamental purposes.

Colour engraving of Narcissus tazetta: ‘Chinese daffodil/Chinese lilly’, from Collection precieuse et enluminée des fleurs… by Pierre Joseph Buchoz, 1776. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Colour engraving of Narcissus tazetta: ‘Chinese daffodil/Chinese lilly’, from Collection precieuse et enluminée des fleurs… by Pierre Joseph Buchoz, 1776. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Wild Daffodils

Wild daffodils first grew in Spain and Portugal before spreading across Europe. Wordsworth’s host of golden daffodils, were almost certainly one of the most pervasive of these wild species, the Narcissus pseudonarcissus.

Engraved illustration of Narcissus sorts, described as pseudo narcissus. Drawn and engraved by Crispijn de Passe the Younger. From Hortus Floridus (Arnheim, 1614). Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Engraved illustration of Narcissus sorts, described as pseudo narcissus. Drawn and engraved by Crispijn de Passe the Younger. From Hortus Floridus (Arnheim, 1614). Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Sometimes called ‘Lent Lillies’, these familiar flowers grew all over Britain until the 19th century. Since then wild populations have declined sharply due to agriculture, woodland clearances and the uprooting of bulbs for gardens.

Watercolour of Narcissus pseudonarcissus (the common daffodil, lent lilly or averill) painted in Sussex by Lilian Snelling, probably in the early 1900s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Watercolour of Narcissus pseudonarcissus (the common daffodil, lent lilly or averill) painted in Sussex by Lilian Snelling, probably in the early 1900s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Daffodils enter the garden

It is quite a surprise that the daffodil first became a popular garden plant in the Tudor and Elizabethan eras. Its natural appearance was far less suited to the geometrical patterns and symmetry of the formal garden styles of the time than other bulb plants like the tulip.

Engraving of a 17th-century garden scene from Hortus Floridus by Crispijn de Passe the Younger, 1614. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Engraving of a 17th-century garden scene from Hortus Floridus by Crispijn de Passe the Younger, 1614. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

However, the daffodil found an important champion in the figure of John Parkinson – who became Apothecary to King James I. His Paradisus Terrestris was the first book in English concerned with the ornamental rather than medicinal uses of plants.

Title page from John Parkinson’s Paradisi in Sole: Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 editon. The title is a pun on Parkinson’s name and translates as ‘Park-in-Sun’s Earthly Paradise.’ Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Title page from John Parkinson’s Paradisi in Sole: Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 editon. The title is a pun on Parkinson’s name and translates as ‘Park-in-Sun’s Earthly Paradise.’ Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

“There hath beene great confusion among many of our modern Writers of Plants in not distinguishing the manifold varieties of Daffodils”.

In his own book, Parkinson identified almost one hundred different varieties of daffodil then growing in England.

Wood engraving of eight Narcissus sorts from John Parkinson’s Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 edition. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Wood engraving of eight Narcissus sorts from John Parkinson’s Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 edition. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Between the late 1600s and early 1800s, many of these old varieties fell out of fashion and were lost forever.

However, Parkinson’s work would later inspire some of the most important daffodil breeders of modern times.

Wood engraving of eight Narcissus sorts from John Parkinson’s Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 edition. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Wood engraving of eight Narcissus sorts from John Parkinson’s Paradisus Terrestris, 1656 edition. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

The first daffodil hybrids

Daffodils are not a quick plant to hybridise as it can take several years to flower them from seed.

The new rage for plant breeding in the early 1800s initially had little room for the daffodil – the focus was on exotic (and expensive) plants like orchids from far-flung parts of the globe.

Watercolour sketch of Narcissus bulb by F.W Burbidge, late 1800s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Watercolour sketch of Narcissus bulb by F.W Burbidge, late 1800s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Daffodil breeding was a quieter revolution. It started in the 1830s, with a Church of England clergyman.

Pencil and watercolour sketches of Narcissus varieties by William Herbert, 1847. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Pencil and watercolour sketches of Narcissus varieties by William Herbert, 1847. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

While Dean of Manchester, William Herbert (1778–1847) successfully cultivated several new daffodil hybrids and pioneered new ways of classifying them.

The Dean’s botanical breakthroughs were admired by Darwin and paved the way for the explosion of daffodil breeding later in the 19th century.

Pencil and watercolour sketches of Narcissus varieties by William Herbert, 1847. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Pencil and watercolour sketches of Narcissus varieties by William Herbert, 1847. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

The Daffodil King

Even after William Herbert, the daffodil continued to be seen as a wild flower that was out of place in the formal gardens that were fashionable in the Victorian era.

There were few British suppliers of daffodil bulbs and few gardeners wanting to buy them.

One of the first to change the tide of popular opinion against the daffodil, was the Scottish nurseryman, Peter Barr (1826 – 1909).

Photograph of Peter Barr, about 1900. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Photograph of Peter Barr, about 1900. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Inspired by the long-lost daffodil varieties that John Parkinson had identified 200 years earlier, Peter Barr built up his own daffodil collection.

He purchased new daffodil hybrids raised by British growers, saving many of them from destruction.

Watercolour of Narcissus Leedsii ‘Superbus’ by William Caparne, about 1884-85. One of a number of paintings that Peter Barr commissioned of the rare collection of daffodils that he had purchased from the prolific English daffodil breeder, Edward Leeds (1802 – 1877). Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Watercolour of Narcissus Leedsii ‘Superbus’ by William Caparne, about 1884-85. One of a number of paintings that Peter Barr commissioned of the rare collection of daffodils that he had purchased from the prolific English daffodil breeder, Edward Leeds (1802 – 1877). Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Barr's successful nursery business and slickly produced bulb catalogues did much to increase the public appetite for daffodils. They also vastly improved the system by which new daffodil hybrids were classified.

A watercolour of a daffodil hybrid named after Peter Barr from his own album of daffodil paintings, early 1900s (artist unknown). The Narcissus ‘Peter Barr’ is described as ‘a grand variety, raised at our nurseries, flower large, bold and handsome’. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

A watercolour of a daffodil hybrid named after Peter Barr from his own album of daffodil paintings, early 1900s (artist unknown). The Narcissus ‘Peter Barr’ is described as ‘a grand variety, raised at our nurseries, flower large, bold and handsome’. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

The first Daffodil Conference

“The Narcissus… is now reasserting its position, and claiming its proper place in the general economy of border decoration, and as a cut flower for furnishing vases”

In 1884, Peter Barr persuaded the RHS to hold its first Daffodil Conference – a visually spectacular event held in a large conservatory at the Society’s South Kensington Gardens. It included breathtaking displays from the likes of Gertrude Jekyll who filled the space with a sea of daffodils in waves of yellow, orange, white and gold

Perhaps most importantly, the Conference led to the establishment of the first RHS Daffodil Committee who would oversee a new official classification framework for daffodils.

From this point on, the RHS would name and register all new Narcissus hybrids.

Daffodils on display at the RHS London Spring Plant and Orchid Show, 2017. Credit: RHS / Luke MacGregor.

Daffodils on display at the RHS London Spring Plant and Orchid Show, 2017. Credit: RHS / Luke MacGregor.

The RHS Daffodil Committee included trailblazing daffodil breeders like Sarah Elizabeth Backhouse (1857–1921).

Already an established daffodil breeder herself, Sarah Elizabeth Dodgson had married into the prolific daffodil growing family, the Backhouses, who bred over 470 new Narcissi hybrids between them.

Photograph of Sarah Elizabeth Backhouse, late 1800s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Photograph of Sarah Elizabeth Backhouse, late 1800s. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections.

Sarah Backhouse pioneered the breeding of red-cupped daffodils and 2 years after her death, her husband named the first ever pink-cupped daffodil in her memory.

Plant portrait of Narcissus ‘Mrs R.O. Backhouse’. Credit: RHS / Philippa Gibson.

Plant portrait of Narcissus ‘Mrs R.O. Backhouse’. Credit: RHS / Philippa Gibson.

Daffodil artists

From early on, artists played an important role in the identification and classification of new daffodil hybrids.

Some of the beautifully accurate daffodil paintings in the RHS Lindley Collections have been used by the current RHS Bulb Committee (the successor to the RHS Daffodil and Tulip Committee) to identify the characteristics of lost daffodil varieties and to add them to the RHS Daffodil Register.

Official RHS portrait of Narcissus ‘Diolite’, which received an award of merit on 6 April 1932, by Elsie Katherine Kohnlein. Credit: RHS / Elsie Katherine Kohnlein

Official RHS portrait of Narcissus ‘Diolite’, which received an award of merit on 6 April 1932, by Elsie Katherine Kohnlein. Credit: RHS / Elsie Katherine Kohnlein

This graceful daffodil portrait is by an unnamed chinaware painter who worked in the factories of the pottery manufacturer, William Copeland (1872–1953).

Watercolour of Narcissus ‘Linnaeus’ and a Pyrenean Narcissus poeticus by an unnamed artist, about 1895–1907. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Watercolour of Narcissus ‘Linnaeus’ and a Pyrenean Narcissus poeticus by an unnamed artist, about 1895–1907. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Copeland was a renowned daffodil breeder who commissioned a large collection of these portraits to capture daffodil varieties grown by himself and others at the turn of the 20th century.

The artist is now lost to history but,in precisely capturing its characteristics, their work has allowed a daffodil that is now out of cultivation to be added to the RHS Daffodil Register.

Watercolour and pencil portrait of Narcissus 'Carnbie’ by Margaret Rebecca Dickinson, 1889. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

Watercolour and pencil portrait of Narcissus 'Carnbie’ by Margaret Rebecca Dickinson, 1889. Credit: RHS Lindley Collections. Click to view on RHS Digital Collections.

This late 19th-century daffodil portrait by the talented botanical artist, Margaret Dickinson, is also a type specimen, capturing the qualities of the now lost Narcissus ‘Carnbie’.

However, this delicate painting is also a reminder of the environmental impact of the daffodil craze at the end of the 19th century.

Dickinson records that the daffodil was grown from a ‘root gathered in Spain by Mr Peter Barr in 1888.’ Later in his career, Barr collected and imported many wild daffodils from Spain and Portugal, which may have enriched daffodil cultivation but had a far less positive impact on native wild populations of daffodils.

Registering Daffodils today

The RHS has been the International Cultivar Registration Authority for Daffodils since 1955.

The Society maintains the International Daffodil Register listing 27,000 named cultivars. The register is searchable online.

New daffodil cultivars are registered by shape and colour. They are divided into 13 divisions according to characteristics such as corona (or 'trumpet') size and the length of the petals.

Beyond the world of the Narcissus specialist, the daffodil has never been more popular. It remains one of our favourite garden plants, appearing in over 80% of British gardens.

Created by RHS Lindley Library.

Based at the Royal Horticultural Society’s headquarters at Vincent Square in London, the Lindley Library holds a world-class collection of horticultural books, journals and botanical art.

Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.